Bridging the Gap between Academia and Policymakers for SDG Implementation Now

“Today, only 15% of the SDG targets are on track, and many are going in reverse. The SDGs need a global rescue plan.”

- UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres -[1]

On Friday, September 15, I visited the Institute for Global Engagement and Empowerment (IGEE), an organization that seeks to facilitate the realization of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The IGEE is housed within Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea. This visit to the IGEE was chosen as the activity for the month’s IEU Interns’ Day programme [2] collectively by me and the other two IEU interns – Zephaniah Danaa and Issahaku Npoagne Tawanbu.

During our visit, we met Dr. Shinki An, a distinguished professor within the Department of Medical Education at Yonsei University and the Chairman of the IGEE. In our conversation, he mentioned that SDGs can be likened to a cascade of interconnected goals and challenges. Addressing a single SDG can undoubtedly exert a positive influence on the other SDGs, and in the same way, a detrimental impact on one SDG can reverberate and affect the others.

According to the analysis of Sachs et al. (2023) [3] in their Sustainable Development Report 2023, numerous interconnected health and geopolitical conflicts have resulted in a worldwide slowdown of SDGs since 2020. Yuan et al.(2023)[4] also argue that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was detrimental to 13 of the 17 SDGs through about ten different pathways. The pursuit of reduced inequality (SDG 10), the achievement of zero hunger (SDG 2), the eradication of poverty (SDG 1), the promotion of good health and well-being (SDG 3), the encouragement of decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), and the eradication of poverty (SDG 1) were the primary goals that were most significantly impacted.

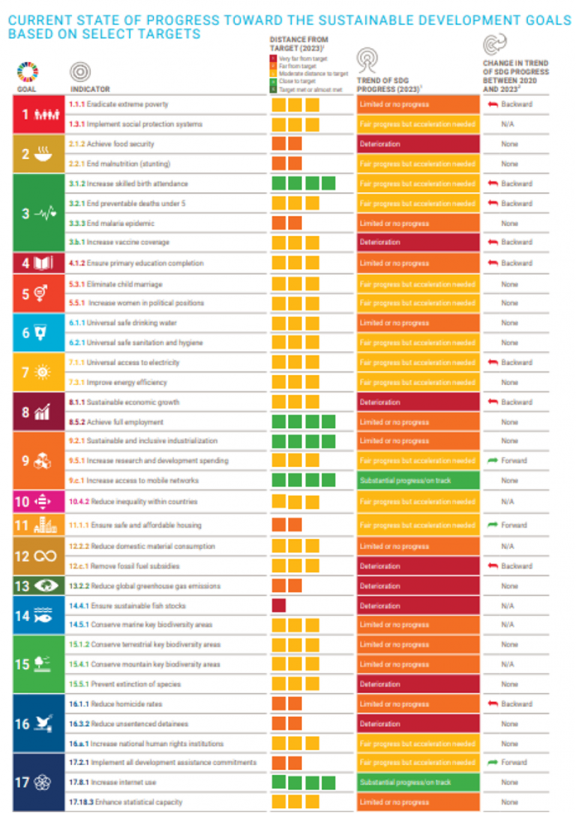

Only 15 per cent of the SDGs that are intended to be achieved by 2030 are currently on track, according to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.[1] This assertion is grounded in an article [5] recently published by the United Nations, which also underscored the fact that it would require approximately 286 years to address and eliminate gender disparities as outlined in Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5), if going at the current pace of things. Based on the Global Sustainable Development Report 20236, it is evident that only a limited number of SDG sub-goals are advancing positively, whereas the majority of SDG sub-goals are either regressing or experiencing negligible changes in their trends (see Figure 1). This is a major shortcoming that needs to be dealt with and resolved immediately. WHEN is NOW, and BY WHOM is EVERYONE.

Figure 1. State of Progress of SDGs Globally.

Source: Global Sustainable Development Report, 2023 [6]

In the latter part of our conversation, Dr. An also stressed how the IGEE seeks to convene both academics and government stakeholders and connect them better through SDG forums. This is done to better disseminate and socialize the study findings and convey them to the target audience that matters most when it comes to SDG implementation —the lawmakers who are in charge of enacting legislation relating to climate change—rather than just students and other scholars.

“It will be much simpler if people in academia would leave the classrooms, institutions, and labs and take a seat in the government,” I exclaimed during my conversation with Dr. An.

I can speak from my experience that this dilemma is real, having worked for many years in both the academia and engineering fields. I have seen that research and statistics have faced political challenges in my home country, the Philippines, for instance. Would it not be more beneficial and faster if our politicians knew everything that there is to know about climate change so that they can effectively solve the global climate crisis? For this reason, I advocate for appointing academics to government or parliamentary seats. Some may argue right away that this is rather ‘unconventional’. However, given the urgency of an impending and very likely failure with the SDGs, isn’t this the time ripe for what one may deem as ‘unconventional’ solutions?

I would say that in developing countries like the Philippines, a ‘new approach’ would be more suitable. In the recent COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines, a private and independent research group called OCTA has emerged as the leading science adviser to the Philippine government. OCTA is consisted of volunteer experts from a multidisciplinary team of academics [7] from two prominent universities in the Philippines – the University of the Philippines and my very own Alma Mater, the University of Santo Tomas. From January 2020 to October 2021 [7], OCTA provided weekly COVID-19 case forecasts: Reproduction Number (R0), positivity rates, hospital capacity at the national, provincial, and local levels as well as quarantine grade options for lockdowns and vaccination rates. All these effectively assisted the government as well as the small business enterprises (SMEs), as they contributed to a business-friendly COVID-19 exit policy for the country. While the government of the Philippines has its own ‘internal’ science advisors, OCTA became the major COVID adviser to the government in the time of COVID crisis.[7]

Another example that illustrates the positive effect of this ‘new approach’ has to do with the Philippines’ quick economic recovery and GDP growth from 2020 to 2021. In terms of the GDP growth rate in the post-COVID-19 era, the Philippines went from -9.5% to 5.7%, becoming the second-best performing country in Southeast Asia in 2021.[8]

This makes me think that having “independent science advisors” for the government or the parliament which could include citizen scientists is one workable solution for us to effectively address climate issues and accelerate SDG implementation, especially in developing nations. As described by Vallejo et al. (2022) [7], these “independent science advisors” can serve as a “challenge function” to government officials and in-house experts, as they can effectively contribute to reviewing and revising future policies to be enacted.

Climate change is a very complex issue that probably none of us can fully comprehend in our lifetime. While scientific data and evidence are the key to any type of intellectual discourse, I also believe that understanding scientific findings alone is not enough to address the complex climate issues. We need political will, political innovation, and most importantly, a forward-looking perspective to address them.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in blogs are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Independent Evaluation Unit of the Green Climate Fund.

[1] Antonio Guterres. (2023). 'Eight years ago, countries gathered in this same #UNGA Hall to adopt the Sustainable Development Goals ...' LinkedIn. Available here.

[2] The Independent Evaluation Unit, Green Climate Fund. (2022). IEU Internship announcement. Available here.

[3] Sachs, J.D., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G. Drumm, E. (2023). Sustainable Development Report 2023. Available here. Last accessed on 9 October 2023.

[4] Yuan, H., Wang, X., Gao, L. et al. (2023). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals has been slowed by indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Commun Earth Environ 4, 184. Available here.

[5] VaSDG Summit 2023. (2023). Available here. Last Accessed on 9 October 2023.

[6] Global Sustainable Development Report. (2023). Available here. Last accessed on 9 October 2023.

[7] Vallejo, B. M., & Ong, R. A. C. (2022). OCTA as an independent science advice provider for COVID-19 in the Philippines. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 104. Available here.

[8] VaBugrov, D. et al (2023). Southeast Asia’s economies: Softening but still strong. Available here. Last accessed on 20 October 2023.