GCF Impact on the Ground: Lessons for Climate Action in Agriculture and Food Security

Smallholder farmers in developing countries are experiencing increasing pressure from changing climate conditions. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events are disrupting agricultural productivity in regions where food security is already fragile. Most smallholder farmers rely on rainfed agriculture and practices developed for past climate conditions, leaving them particularly vulnerable to these shifts.

This vulnerability makes agriculture a critical focus for climate finance institutions like the Green Climate Fund (GCF). The sector is not only deeply affected by climate change but also contributes nearly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2024). Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) has emerged as a widely promoted solution to build resilience and reduce emissions simultaneously.

However, the adoption of such practices on the ground remains uneven. Research on agricultural technology adoption in developing countries points to three persistent constraints: limited access to credit, information gaps and risk and insurance market failures (Magruder 2018). These barriers may be particularly relevant for climate adaptation technologies, as farmers are often unsure whether new practices will perform reliably under increasingly unpredictable weather patterns.

The Independent Evaluation Unit (IEU) continues to assess how different interventions within the GCF’s portfolio influence the adoption of climate-resilient practices in agriculture and contribute to building climate resilience. The IEU directly engages with the project teams to prepare learning-oriented, real-time impact assessments of GCF projects (LORTA) through its initiative on the same.

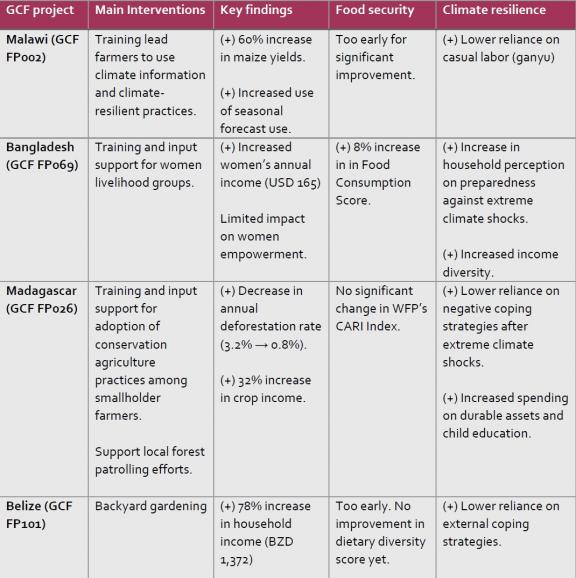

In this blog, we will take a closer look at the impact evaluations that explore a range of approaches, from supporting women’s livelihoods in coastal Bangladesh to promoting sustainable land use in Madagascar, across four countries: Bangladesh, Malawi, Madagascar, and Belize. Together, the findings suggest that targeted interventions can drive meaningful adoption, but that outcomes vary depending on local conditions, how support is delivered, and who is reached. What have we learnt about impact on the ground especially from four recently completed impact evaluations?

Impact Insight 1: Training that addresses more than technical skills in Bangladesh

A first study, conducted in climate-vulnerable coastal communities in Bangladesh, uses a randomized controlled trial to estimate the impact of supporting women’s livelihood groups on the adoption of climate-resilient practices. These communities face increasing salinity due to rising sea levels, making traditional agriculture less viable and highlighting the need for alternative livelihood options. In response, the gender-responsive coastal adaptation project implemented by UNDP (GCF FP069) supported women’s livelihoods groups with training and inputs for practices such as homestead gardening, floating gardens, sesame production, and crab farming.

The results were substantial: participating women experienced an average increase of 14,000 BDT (USD 165) in annual income and an 8 per cent improvement in household food consumption scores compared to the control group. These findings indicate meaningful gains in both economic and food security outcomes. High adoption rates persisted even two years after project implementation, largely driven by well-integrated training efforts (FP069: Impact Evaluation Brief). However, women’s autonomy over the use of income remained limited, underscoring the importance of complementary support beyond technical skills. The IEU’s 2022 Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Life Skills Training Interventions for the Empowerment of Women in Developing Countries underscores this finding. The review concludes that life skills training, aimed at building psychosocial competencies such as self-awareness, interpersonal communication, and decision-making, can modestly enhance women’s empowerment, particularly when delivered as part of broader interventions that also provide technical support (Independent Evaluation Unit 2022).

Impact Insight 2: Peer learning and behavioural change in Malawi

A second study, conducted in rural Malawi, aimed to address a different kind of barrier to CSA adoption. The Participatory Integrated Climate Services for Agriculture (PICSA) component of the GCF-funded M-CLIMES project recognized that farmers often rely on traditional weather indicators and resist new climate information, creating a behavioural barrier to adopting climate-resilient practices.

Using a "training of trainers" approach, the intervention equipped lead farmers with climate information and new farming techniques, who then shared this knowledge within their communities. The approach proved effective at changing agricultural practices across the broader community. Lead farmers who successfully implemented new practices were able to build trust regarding the new practice within the community, demonstrating that behavioural science principles, particularly the importance of trusted messengers, can be important for scaling new agricultural practices (FP002: Impact Evaluation Brief). This finding suggests that the manner in which information is delivered can be just as important as the information itself.

Impact Insight 3: Women's associations and sustained adoption in Madagascar

Across several projects, women often play an important role in driving climate adaptation efforts, but they also face distinct barriers that require targeted support. In Rwanda (FP073), impact evaluation findings from the Green Gicumbi project showed that the adoption of climate-resilient agricultural practices was significantly higher among female-headed project households (FP073: Impact Evaluation Brief).

Endline findings from the Sustainable Landscapes in Eastern Madagascar project (GCF FP026) highlighted both the challenges and opportunities faced by female farmers. While time and labour constraints limited the sustained use of labour- and resource-intensive conservation practices for female-headed households, the presence of women’s associations offered a promising pathway forward. These groups enabled collective action, such as labour sharing, joint input purchases, and cooperative marketing, that helped sustain adoption. This highlights the need for gender-responsive CSA project design that addresses the specific constraints faced by women farmers (FP026: Impact Insights).

Selected impacts highlighted from the IEU’s impact evaluation portfolio

Source: Analysis done by the LORTA team.

However, important challenges remain across multiple engagements and impact evaluations of climate action:

Limited impact on food security outcomes. Despite increases in agricultural productivity and income, the impact evaluations across LORTA projects found limited improvements in standardized food security measures. In Belize, Backyard Gardens project (part of GCF FP101) led to a 78 percent increase in household income but showed minimal change in overall dietary diversity. This suggests that income gains alone may be insufficient to improve long-term food security, and that complementary, nutrition-sensitive interventions may be necessary.

Risk and uncertainty remain significant barriers. Farmers often hesitate to invest in new agricultural practices when outcomes are uncertain, especially without insurance or safety nets. A common concern captures this hesitation: “What if I invest in this new seed, but it doesn’t rain?” Findings from Madagascar (GCF FP026) show that after extreme shocks like cyclones, some farmers questioned the effectiveness of promoted practices, indicating that extreme weather events can erode confidence and reduce long-term adoption.

One approach being explored is the integration of crop insurance into agricultural microcredit provided for small-scale farmers. For example, Tanzania’s TACATDP project (GCF FP179) includes a bundled model where farmers access index-based insurance alongside microcredit provided through the project partner. While the impact evaluation study is still at the data collection stage, this structure aims to reduce perceived risk for both farmers and financial institutions, potentially encouraging more widespread and sustained adoption of climate-resilient practices.

Broader infrastructure for sustainability. Sustained adoption of CSA practices often depends on access to infrastructure. In Madagascar (FP026), households in remote areas with poor road access and weak market integration were less likely to continue conservation agriculture once project support ended. These findings highlight the importance of complementing technical assistance with investments in roads, market access, and other enabling systems.

Learning for Impact: Looking Ahead to B.42

The upcoming GCF Board meeting in Papua New Guinea (B.42) presents an opportunity to reflect on how adaptation investments can be made more effective and evidence driven. A total of 19 projects have been proposed, requesting USD 1.3 billion in GCF funding and representing a total project value of USD 3.8 billion including co-financing. Of these, 10 are adaptation-only projects. At B.42, 94 per cent of adaptation funding is directed to the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and African States.

This emphasis is encouraging, particularly with strong representation from the SIDS, including a health project in Micronesia, a fisheries intervention in Saint Lucia, a climate information initiative in the Maldives, and REDD+ results-based payments in Papua New Guinea which are pending Board-approval.. However, as stated in past IEU evaluations, the operational realities of working in SIDS contexts, including high logistical and transport costs, dispersed populations, and limited data systems, underscore the importance of building robust, flexible approaches to monitoring and evaluation. Findings from the IEU’s impact evaluations suggest several ways to support more effective and evidence-informed adaptation programming, focusing on three key areas:

Firstly, early planning is key to ensure robust impact evaluations. Through the IEU’s LORTA work, a selected number of newly approved GCF projects are invited each year to participate in a Design Workshop hosted by IEU, where project teams work closely with IEU staffs to develop context-specific impact evaluation designs. This process helps align impact evaluation with the project’s overall monitoring and evaluation framework and ensures that key considerations, such as baseline data collection, comparison groups, and measurable indicators, are integrated from the start (Independent Evaluation Unit 2025a).

A recently published Evaluability Study by the IEU found persistent medium-risk ratings for credible reporting, particularly on investment criteria, highlighting ongoing gaps in monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and budget alignment. An early integration of impact evaluation frameworks during project development remains critical to strengthen evidence generation, as proactive planning directly enhances evaluability while reducing costly mid-term adjustments. On the other hand, the study also shows reassuring positive trends in the area of data collection and reporting, with substantial improvements in how projects describe the plans to gather, analyse and report data.

Secondly, resilience needs better metrics. Resilience is a central goal of many GCF projects, yet it remains difficult to define and measure resilience in practice. Based on the IEU’s experience, climate resilience is best understood in relation to the specific shocks or stresses that households face. Developing standard indicators while allowing for contextual flexibility will be key to tracking resilience more systematically across projects.

Lastly, track co-benefits in Health, Wellbeing, Food & Water Security (HWFW)-related areas. Even when projects are not explicitly tagged under the HWFW result area of GCF, they often generate valuable co-benefits, such as improved nutrition, livelihoods, or health. However, these outcomes are often overlooked due to a lack of standardized indicators. Moving forward, developing shared metrics and equipping the Accredited Entities with practical guidance on how to collect and report these outcomes systematically will be essential to make HWFW-related co-benefits more visible and comparable across the GCF portfolio (IEU evaluation, 2025b).

References:

Independent Evaluation Unit. 2022. “Effectiveness of Life Skills Training Interventions for the Empowerment of Women in Developing Countries: Systematic Review.” IEU Learning Paper. Sondo, South Korea: Independent Evaluation Unit, Green Climate Fund. https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/document/systematic-review-effectiveness-l....

———. 2025a. “2024 Synthesis Report of the Learning-Oriented Real-Time Impact Assessment (LORTA) Programme.” GCF/B.41/Inf.09 Annex II. Sondo, South Korea: Independent Evaluation Unit, Green Climate Fund. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/09-report-act....

———. 2025b. “Final Report of the Independent Evaluation of the GCF’s Result Area ‘Health and Wellbeing, and Food and Water Security’ (HWFW).” Evaluation report 21. Sondo, South Korea: Independent Evaluation Unit, Green Climate Fund. https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/document/final-report-hwfw2024.

Magruder, J. R. 2018. An assessment of experimental evidence on agricultural technology adoption in developing countries. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 10(1), 299-316.