A Behaviour and Design Toolbox

What is your favorite bias? This is perhaps the oddest yet one of the most frequently asked questions you may hear among behavioural scientists across different sectors. The Unit’s Learning Oriented Real-Time Impact Assessment (LORTA) programme collaborates with its partners to better understand behavioural science (BeSci) in developing countries and how these insights might elevate the effectiveness of climate projects.

In integrating BeSci in developing countries, it is crucial to first acknowledge that mainstream BeSci has largely been shaped by WEIRD countries, as the Busara Center for Behavioral Economics refers to them. These are Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic countries. During the 2021 LORTA Virtual Design Workshop (VDW), the BaD Lab and Busara hosted a series of webinars for the GCF’s Direct Access Entities on how to integrate behavioural science in addressing climate change. During these webinars, Busara presented that BeSci is not only about understanding human decision-making processes, but also about better understanding the predictably irrational decisions that human nature consistently moves in.

Theories of political science and traditional economics largely depend on rational thought alone. BeSci, on the other hand, begins with a fundamental acknowledgement that humans are prone to subjectivity and irrational thinking. Each of us holds a cognitive framework shaped by socio-culturally formed biases. For instance, studying world history from European education models does not equate to the same understanding of world history from African perspectives. As Dan Ariely has famously explained, despite intentions to always make rational decisions, human behaviour is so consistently irrational that we are predictably irrational. Thus, BeSci facilitates our understanding of predictably irrational decision-making processes that influence developmental or environmental interventions.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres recently released a Guidance Note urging UN Entities to invest in BeSci as the “evidence-based understanding of how people actually behave, make decisions and respond to programmes and policies, (in addition to) diagnosing barriers and understanding enablers that help people achieve their aims,” with specific mention of environmental objectives.

The Unit has created a digital Behaviour and Design Toolbox to synthesize evidence and develop guidance on how to evaluate behavioural changes activated by GCF projects. It was built with support from Busara as well as Rare’s Center for Behavior and the Environment. The Toolbox currently contains two parts. Part 1 introduces biases and heuristics to illustrate how behavioural barriers can be overcome in climate projects. It builds on three biases from the BaD Lab’s learning paper, “Going the Last Mile: Behavioural Science and Investments in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation” (Kruger and Puri, 2020), which are i) perceived distance, ii) cognitive dissonance, and iii) framing. Evidence on the human brain demonstrates that biases such as perceiving climate change as a futuristic or geographically distant problem, discomfort about a gap between necessary actions and individual capacity, or mitigative options that have been framed in a disastrous tone, will inevitably build barriers that prevent immediate decisions or actions to counter climate change. However, the great news about biases, as the Toolbox will show, is that identifying them actually presents opportunities for the same biases to be turned around as interventions.

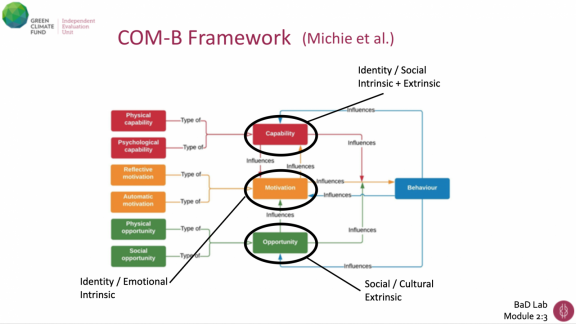

Part 2 presents factors that influence a person’s decision-making framework, and breaks down behaviour according to the COM-B Framework of capabilities, opportunities, and motivation, creating pathways to build new behaviours. Mapping out the COM-B features found within the scope of a GCF project helps to support alignment of the individual or household behaviours alongside the project’s proposed activities, in order to strengthen the sustainability of its impact and effectiveness.

One of the biases I’m most intrigued by is the normalcy bias. This bias refers to people’s ability to face disasters or serious threats by holding the past as the ultimate standard for ‘normal’, thus bypassing the severity of warnings. This global pandemic has propelled us to make considerations in a new direction of anticipating a normalcy we are not yet familiar with. In fact, truly innovative planning and strategies will take center stage in the new normal we anticipate for the path ahead. The pandemic has raised some significant hurdles for both the public and private sector, as well as challenges for the accredited entities in reaching the developmental and environmental objectives that are outlined in the funding proposals (FPs). As these organizations continue to re-design or re-assess a new normal, may the Toolbox shed a bright light on how to further engage with the human lives impacted by the project activities.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the blog are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Independent Evaluation Unit of the Green Climate Fund.