Desert with a dirt road

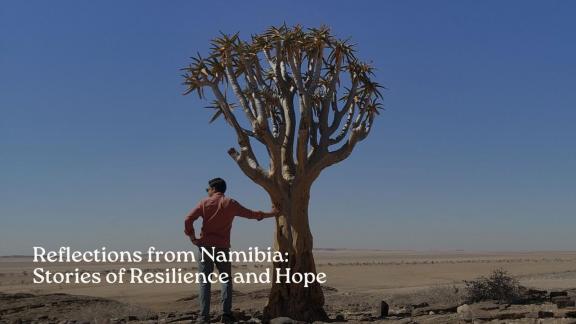

IEU staff member Archi Rastogi shares reflection while on an evaluation visit to Namibia.

The landscape of Namibia is like the tragic matriarch of an opera. She had been battered and bruised by the unseen villains of sun and drought, and simply by time. Yet she stands tall and imposing, graceful and dignified. She remains defiant no matter the travesty. You can tell she is formidable and unflinching, and yet arrestingly beautiful. When you reach an elevation, it is easy to see that the landscape stretches the same way as far as the eye can see. No imposing mountains or gushing waters; only a vast expanse of savanna and sand and rocks and grass the color of gold. No water for miles, not even a blade of green to protect from the sun.

And then there are communities that live embedded within this unforgiving landscape. You drive for hours and seldom come across another person. But the communities are there – sparsely but definitely spread across the landscape. How does the GCF work for these communities? Is the GCF effective in its orientation towards the result area of health, well-being, food and water-security? You are here to ask some of these questions as part of an ongoing IEU evaluation.

Not a drop to drink

During a 5-day official visit, you drive perhaps 2,000 km and yet barely scratch the surface. The landscape is so barren and so parched, and yet the most remarkable sight, that it distracts. You want to exchange notes with your travel companion on the evaluation, and instead stare at the view. You take all manner of roads, metal road and gravel road, dirt road and sandy paths, and you lose your way. At one point, an elderly man in a bright red t-shirt gives you directions. In the background is a metal shed where he presumably lives. But his beaming and toothless smile is hard to forget. He becomes a central character for your discussions. You use a fictionalized version of grandpa as a central character of your imagined development context. You wonder to yourselves about how public services reach Grandpa? Where does Grandpa get access to drinking water, or how far is his closest medical service? You ask yourself if you were the State – or if you were the GCF – how would you reach him? To fill grandpa’s story, we have to think of the lead characters – the landscape and the drought.

If the landscape is a lead operatic character, drought is the main villain that appears frequently and with brute force. There are many dry riverbeds within the landscape. They fill up fast during a rain upstream, and the flash floods destroy areas downstream. (Nature does have an oddly cruel sense of distributive justice, as you know from climate finance.) Nearly every evaluation interviewee brings up drought. The last time is rained in Windhoek was in February; it is August now. If this a drastic national emergency, how would grandpa cope? A report by IFRC identifies the following as primary coping mechanisms: reduce number of meals eaten, sell animals, remove children from school, and borrow from neighbors. Your own interviews reveal stories of starving people and livestock, health issues, and survival. Those that do cope with the drought, find themselves one more catastrophe away from collapse.

Clearly grandpa is far away from any private sector. Only the public sector can reach grandpa, but the public sector is already facing a hefty bill because of the drought. Drought has been brutal in the past ten years, and the public sector is essentially depleted. The infrastructure was inherited at the time of independence, more than 30 years ago. It is costly to maintain, even if you leave aside the costs imposed by sustained drought.

How does the GCF result area apply here? Hypothetically, when GCF resources reach grandpa, it does not matter whether these are intended for one or the other result area. For grandpa, access to water is a larger problem of survival, where the distinction is impossible between livelihood, wellbeing, health and general resilience. It is one grand issue, somewhat impossible to parse into separately fund-able pieces. Development wisdom first argued for separating the issues (into SDGs, for example) and now the complexity is visible. Have we come a full circle?

The rainbow of hope

During your week here, you meet all flavors of hope. Hope has audacity. Hope is contagious. Hope even has indignation.

When you meet community members, some of them share a laugh at the funny sound of your name. Once they settle into serious conversation, you are infected by their hope of a bright future. “We want to stand on our own feet”, says a woman respodent [paraphrased for annonymity] involved with a project that has had halting success with its vegetable garden and chicken farm. In another case, a member of the community is bursting with hope to contribute to the GDP of the country. Development workers in the capital are indignant at the GCF’s difficult procedures, but also filled with hope. One interviewee gets choked up as she describes the impact of her GCF project on communities. The kind of impact to families and children and women, and really in changing life; perhaps Grandpa may be a beneficiary. A staff member of a development agency sends you WhatsApp message after the evaluation interview to thank you for listening. “Nobody comes to us and listens to us”. Another tells you that the GCF has come to the right party; it just needs to have patience to see the results and allow room for mistakes. Together, they fill you with honeyed hope.

At the end it appears that the portfolio of GCF projects in Namibia would have developed regardless of the GCF results area. The government and national institutions have developed a portfolio with a focus on their own needs and the needs of Grandpa, somewhat irrespective of the GCF nomenclature of results areas. As an evaluator you are agnostic; as a climate worker you are filled with contagious hope that good impact is finding its way.

Handbag diplomacy

It is time to leave Grandpa, to go home and analyze what you found for GCF results area. It is your final day in the country. You are out shopping from the crafts market, where you see traditionally dressed women. The Himba people were traditionally herders, and many have been settled down. Many have taken to selling arts and crafts. Some Himba women come to the crafts markets in traditional attire, and tourists can get a picture with them for a fee, not unlike the gladiators and warriors outside the Colosseum or Spiderman at Times Square. In this case, you can’t make up your mind about the propriety of it all. So, you don’t get a picture. But you do want to buy some souvenirs. You walk up to a seller, select your wares, the seller exhorts his wife, who is the only authority on final prices. She doesn’t like your offer, but she likes your canvas sling bag, and why does nobody ever give her a gift. Oh, how lovely is your bag. You take the hint. An exchange ensues, which also seals the deal on the souvenirs.

Is this a deal on tiny souvenirs, or are you witnessing a microcosm of her astute adaptability, flexibility, and a sense of modesty coupled with an ability get what she needs? Perhaps her resourcefulness represent her community’s resilience in the context of the beautiful landscape and the brutal drought. Are you seeing a masterful use of remarkable ingenuity? Or perhaps you are just overthinking a simple transaction.

If you – dear reader – find yourself in the Namibian landscape and spot a lady with a white-colored bag with an anachronous Korean landscape, say hello to Martha, this author’s Namibian sister.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in blogs are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Independent Evaluation Unit of the Green Climate Fund. Names are changed for anonymity.

The visit to Namibia was part of the IEU Independent Evaluation of the GCF's "Health, Well-being, Food and Water Security" Result Area. The case study report will be available during the course of the evaluation.